The financial plan is an assessment of funding needs over the next 3 to 5 years.

The following chapters explain more in detail:

All organizations need to plan their budgets at least annually, but those organizations practicing more advanced asset management are likely to have planned their budgets for the next three to five years if not longer. Undertaking road maintenance clearly requires a financial commitment from senior leaders in the organization. This financial commitment is needed to fund the staffing of the organization and routine and cyclical maintenance activities as well as periodic maintenance activities. Where organizations undertake road maintenance themselves, the financial plan should also include budgeting for physical resources to undertake the maintenance activities that include labour, materials, and construction equipment.

The budget allocated may come from different sources that fund both the maintenance activities (including routine maintenance) and the capital activities (investment). This funding may come directly from the central government, donor organizations, local governments and municipalities, or tolls. The financial plan will be used to demonstrate the activities that the budget will be allocated to and why the budget is needed.

The financial plan should be part of the asset management plan. It should be informed by lifecycle planning and the maintenance standards adopted by the organization.

The financial plan sets out the approach that the organization will use to allocate the budget that has been provided. Depending on the maturity of the asset management organization, the financial plan should be undertaken for the short (basic), medium (proficient), and long (advanced) term. This will give the organization a transparent view of its financial commitment. The financial plan should provide details of the funding required to be delivered. The breakdown of the financial plan should align with the work types and volumes. The plan should also include the impact of different levels of funding on the network, such as the impact on performance.

When governments or senior leaders in the organization have not committed to the budget, the financial plan must demonstrate the funding required to meet the performance set out in the asset management policy and strategy. The financial plan, however, will only be based on the planned work that will be undertaken when the organization has committed to the budget. This planned work may be adjusted depending on the budget allocated. It should be noted that lifecycle planning, described in Chapter 2.4,2 Lifecycle Planning, should be used to determine the most cost-effective means of achieving the financial plan.

When setting and agreeing on budgets with the senior leaders in the organization, it is important that asset managers make a strong and robust case to invest in asset maintenance. The financial plan should therefore demonstrate that the transportation infrastructure maintenance activity can only be efficient if it is planned in the long term and the asset management practices described in this guide are adopted.

A practical example of demonstrating the benefits of long-term funding include investment in preventative maintenance techniques, which may provide significant value for money when compared to more expensive treatments that are applied based on a “worst first” approach.

Ideally, the most effective financial plans cover between 5 and 15 years. This means that the allocation of resources, and especially of financial resources, has to be anticipated well in advance so organizations can plan accordingly.

The financial plan therefore supports organizations in identifying both the required and available financial resources in future years. As such, it is an essential document to support the exchanges between the senior leaders in the organization, road owners, financing authorities, and those responsible for asset management. Its main function is to do the following:

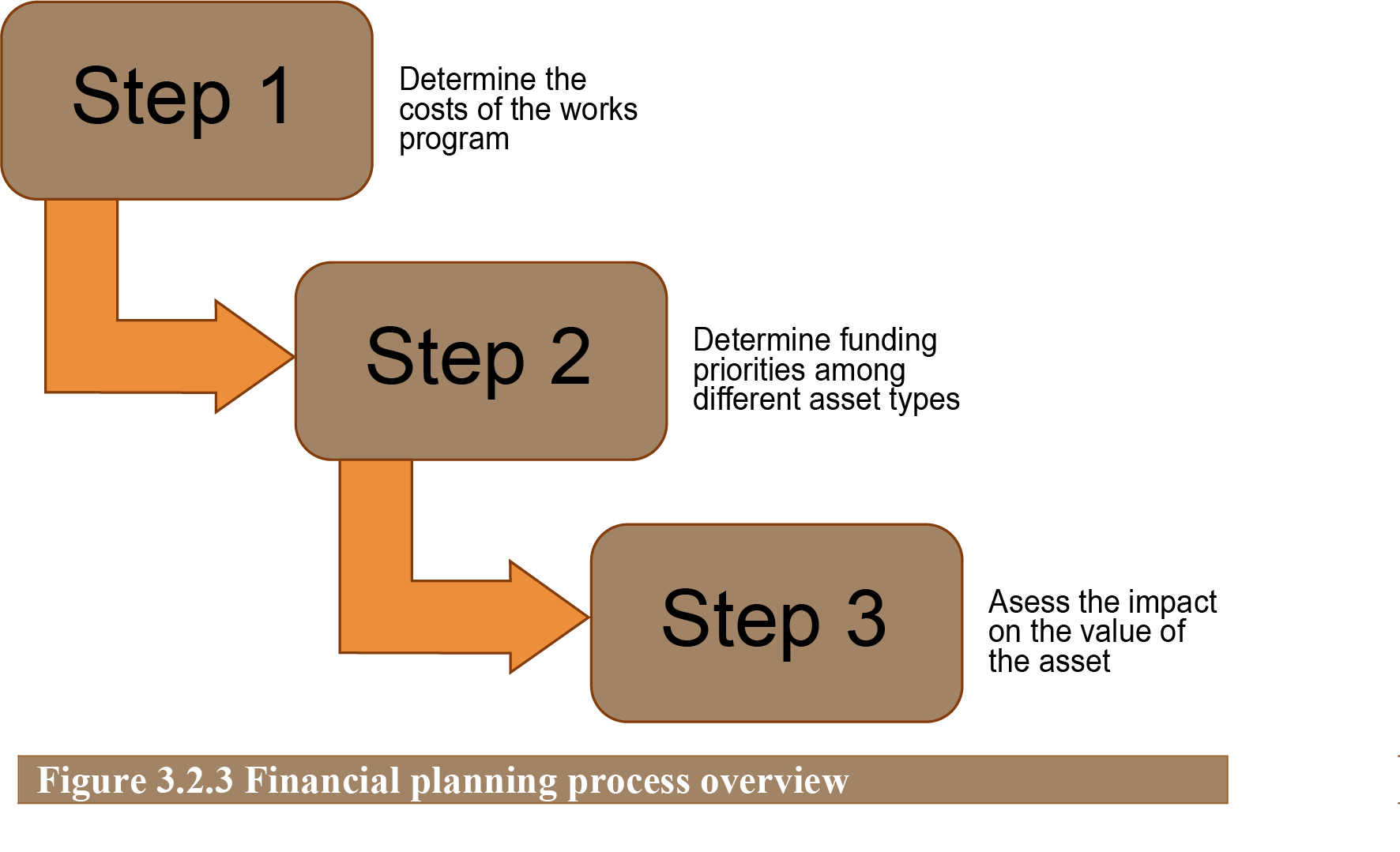

The process of building a financial plan is illustrated in Figure 3.2.3.

Step 1. Determining the cost of proposed works

The financial plan should build on the works plans (AMEC 2013) that contain the maintenance schemes the organization is required to undertake. Works plans are described in greater detail in section 3.4. The works plan should contain the schemes that have been prioritized according to the policy of the organization at least for the upcoming year but ideally for the next three to five years. It may also contain a number of different work plans to be implemented depending on the funding provided (Lepert 2012). Ideally, each asset group, such as pavements, structures, or lighting, should have determined costs of its own work plan.

Step 2. Allocating the funds among program areas

Depending on the funding available, there may be a requirement to allocate budgets to each asset type, such as pavements or structures, from a single capital allocation. Traditionally, many organizations have allocated budgets on a historical basis. For example, roads may get 60% of the maintenance budget and structures 20%. The financial plan, therefore, may be based on historical spending levels. More advanced organizations may consider prioritizing their assets to ensure that both those assets most in need of funding for the organization to meet its strategic priorities and those assets that may be critical towards the organization, such as strategic bridges, are funded. Such an approach to developing financial plans will ensure that the organization gets the greatest economic return. In doing so, however, the organization may have to accept that there may also be political requirements to address.

One approach to allocate funding among different assets may be based on ensuring that the optimum performance rather than the maximum performance is achieved for each asset. In organizations with a mature asset management program, this approach can be developed through a performance management framework that links assets to strategic and funding priorities.

For example, should a bridge fall down, even if the pavement on both sides is new the road will be totally closed to traffic. Conversely, should the pavement on both sides of a new bridge be in drastically bad condition, the traffic over the bridge will be greatly affected. This example illustrates a holistic consideration from each asset group to meet wider strategic objectives on the same route. In such an approach, consistency can be achieved by considering a common level of service for that route. An alternative approach may be to consider the risk associated with the poor performance of an asset group on that route. Generally, pavement management and bridge management are key asset concerns that need to be looked at holistically. Pavement deterioration is visible to road users and may be more politically sensitive for road organizations. Bridge deterioration is managed in terms of the risk and criticality of that structure to the local and national economy.

Step 2 becomes a challenge when budgets are constrained and there is insufficient funding to meet the required performance or eliminate the backlog of maintenance, which is the case most of the time.

Step 3. Assessing financial sustainability

It is important that the financial plan preserves the value of the assets in the organization’s ownership as much as possible. It is accepted that investment in roads contributes to the economy through well-maintained accessible roads. Depending on the organization and its accounting practices, the financial plan may also impact the balance sheet of the organization. For example, if the financial plan does not maintain the network in steady state condition, but because of known funding constraints the plan is unable to arrest deterioration, then the value of the assets will depreciate. This may result in additional financial charges to the organizations in order to fund this depreciation. Asset valuation is described in greater detail in Chapter 3.3 Asset Valuation. Developing a financial plan that is sustainable should be one objective of the organization.

In the U.S., the assessment of the financial sustainability of the transportation system currently uses the GASB 34 modified approach. GASB 34 requires state and local governments to report the value of their infrastructure assets in their annual financial report on an accrual accounting basis. Under this method, the loss in value of an asset is spread across the asset’s useful lifetime. In this way, the budget for maintenance intervention appears in parallel with the amount of loss in asset depreciation. More maintenance should, normally, induce less asset depreciation. In other words, an increase in asset maintenance could be balanced, to a certain extent, by a decrease of asset depreciation.

This approach does not take into account the benefits of maintaining the infrastructure asset on the total cost, including transportation costs for freight and people, environmental impacts, etc., which a cost-benefit analysis (CBA) approach can. GASB 34 also does not take into account the risks inherent in the planning process (e.g., unexpected reduction of budget, growth of traffic, severe climate events), which risk analysis does. More recently (2012), the MAP-21 legislation has required local authorities to provide the following information (Applied Pavement Technology 2013):

With this legislation, it is recognized that assessing financial sustainability requires preliminary lifecycle cost considerations and risk management.

The financial plan describes the amount of funding expected over the next 3 to 5 years and where it will come from (eventually, component by component). Such plan documents any assumptions made in preparing the plan. Therefore, it will help to evaluate the uncertainties and risks affecting the expected budget.

Financial plans are prepared to inform the planning and management of an organization’s maintenance responsibilities (PIARC 2006). Financial plans should also be used to make the case to senior leaders for investment in transportation infrastructure. In order to secure the necessary funding, it is important that a robust business case is made for the investment needs. The case should be supported by including the appropriate transportation infrastructure information described in this guide. In addition, it is suggested that the consequences of underfunding by, say, 10 %, 20 %, and 30 % should be presented in terms of the following:

This information helps the decision making process for allocating funds because it considerably strengthens the business case for investment in the maintenance of highway structures.

Applied Pavement Technology, Inc. 2013. Minnesota DOT Work Plan for Developing a Transportation Asset Management Plan. Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) Asset Management Steering Committee and Project Management Team (PMT). St. Paul, Minnesota, US.

AMEC Environment & Infrastructure, Inc., Cambridge Systematics, Inc., "New York State DOT Work Plan for Developing a TAMP", FHWA, July 2013.

Ph. Lepert, "Road maintenance policy based on an expert asset management system - Concept and case study", SURF'2012, Norfolk, USA, September 2012.

PIARC 2006. An Overview of PIARC Studies on Financing Road System Investments, Alston, Sheri (https://www.piarc.org/ressources/publications/3/4849,RR332-IntroAlston.pdf).

PIARC, TC-D1.2, "High Level Management Indicators", PIARC report, Paris, France, October 2011

Ph. Lepert, F. Brillet, "The overall effects of road works on global warming gas emissions", 1361-9209/$ - Published by Elsevier Ltd., doi:10.1016/j.trd.2009.08.02.

A. Weninger-Vycudil , Ph. Lepert, "EVITA: Environmental Key Performances Indicators", EPAM3, Copenhagen, Malmö, Sweden, September 2012.

These practices have been tested in several instances and case studies are being prepared. They will be presented here when available. If you want to share a case study, please contact assetmanagementmanual@piarc.org.