Many road organizations around the world still operate using a silo-like structure, in which the various physical and operational issues such as road capacity and road safety are managed separately, i.e. with no consideration of common strategic objectives. Consequently, organizations tend to focus on the short-term, project-level management of road assets, which, in a context marked by resource shortage and competing stakeholder demands, make it difficult to attain performance goals at the network level.

This chapter discusses several topics related to adapting the structure of a road organization to unleash the potential of asset management, and support the organization in achieving its objectives. These topics comprise leadership and culture, self-assessment of current asset management practice, asset management champions and their crucial role in promoting the required changes, and the organizational structure suitable to implementing asset management. Also, it covers the personnel competencies that should be developed to meet the requirements of asset management, which fall under a number of knowledge areas thus showing the multidisciplinary nature of asset management.

For asset management to be successful, a road organization must have in place a corporate structure that facilitates the implementation and delivery of asset management by appropriately empowered and competent staff (UKRLG and HMEP 2013). This organizational structure must be fully supported by the leadership.

The assessment of current asset management practices may reveal the need for an important corporate change to attain the potential of asset management. Depending on the differences between actual and recommended practice, the implementation of a comprehensive change strategy may be required, which should be driven by the organization trying to reach the level of maturity.

The change strategy has to identify what needs to be done and how the organization’s executives will involve and motivate staff in achieving the benefits pursued. Typical processes of this corporate change include integrating asset management into business processes and organizational culture, establishing asset management roles, and setting performance management standards (FHWA Transportation Asset Management Expert Task Group 2013). These standards, in particular, may be supported by agency agreements with the government.

Many road organizations around the world still function based on a silo-like organizational structure, in which the areas responsible for managing the various asset types (pavements, bridges, slopes, and so on) operate almost in isolation, without an integrated vision to achieve the corporate objectives. Asset management aims at aligning and linking processes so that all business units within an agency operate in a coordinated fashion rather than independently (FHWA 2012), based on a unified view of asset management policy and strategy taken at the leadership level (UKRLG and HMEP 2013).

Frequently, adopting the structure for asset management will present greater challenges than putting to work new technical or analytical procedures (FHWA 2012). This might be particularly the case with developing countries, where the resources and staff necessary for the institutional change may not be available, thus inhibiting the implementation of asset management. In such circumstances, greater effort is usually required from the supporters of change to make the case for asset management.

The changes required to adopt the asset management framework usually involve a deep transformation of the road organization, which should be supported by strong leadership and commitment. Such leadership must be in place from the moment the need to implement asset management is first recognized so that the organization conducts, as a first step, a self-assessment exercise for identifying the required changes. Very often, the initial steps towards a corporate transformation are actively promoted by asset management champions.

Results from the self-assessment exercise typically include new or modified business processes, workflows, activities, or tools that should be put into practice. In general, organizational structures existing prior to the adoption of asset management are inappropriate to accommodate those innovations smoothly, and, therefore, the shape of the road organization must be rethought to establish the roles and information flows that will better serve the chosen approach to asset management. Moreover, the new roles will likely require new staff competencies that extend far beyond the traditional areas of road engineering.

The following sections provide greater detail concerning leadership and culture, self-assessment, champions, asset management roles, and competency requirements.

Leadership has a strong influence on the culture and behavior of all organizations. Clear direction and priorities will ensure that both significant and apparently minor decisions made across the organization support a consistent approach to achieve the business objectives. Such decisions include appropriate investment decisions to reflect the asset management strategy (UKRLG and HMEP 2013).

Below is a list of some of relevant aspects of leadership and organizational culture as applied to asset management:

The self-assessment’s aim is to benchmark the current asset management practices of the organization and identify specific opportunities for improvement (Cambridge Systematics et al. 2002). The main objectives of self-assessment include the following:

One of the most important steps in implementing asset management is to identify the organizational policies and goals to be achieved, which will define the agency’s most important priorities. Asset management is a customer-focused, goal-driven management and decision-making process. Organizational goals, policies, and budgets establish a consistent evaluative philosophy. Goals and performance measures are the levers that drive the decision framework, establishing investment scenarios that reflect levels of service and making resource commitments consistent with the perceived needs of stakeholders. Analysis procedures regarding alternative options are used within this framework (FHWA 2012).

It seems to be universal that, at least in the early stages of implementing an asset management framework, there will be a need for a champion, who can be anyone with sufficient interest and influence to promote organizational changes. A champion may be designated by someone in top-level management or he may simply emerge from among the members of the involved groups. In any case, a champion is one who does not rest until the mission is accomplished. Candidate champions include the following:

The champion for implementing an asset management framework will face the challenge of prevailing in any deliberations and debates about why such a differentiated approach is needed at all.

Arguments about the unique significance of the road system, the benefits (and complexity) of a risk-based approach, the need for mitigation strategies and contingency plans, and the interests of stakeholders are likely to be relevant to the champion (Cambridge Systematics et al. 2009).

In designing the most suitable organizational structure to support asset management, road organizations may choose either a centralized or a decentralized approach. While the former facilitates consistency of processes and work methods, it also entails the risk of making asset management appear remote for the areas responsible of service delivery, which may not fully understand the policies defined centrally. On the other hand, in some circumstances a decentralized structure may result in a fragmented asset management approach and culture.

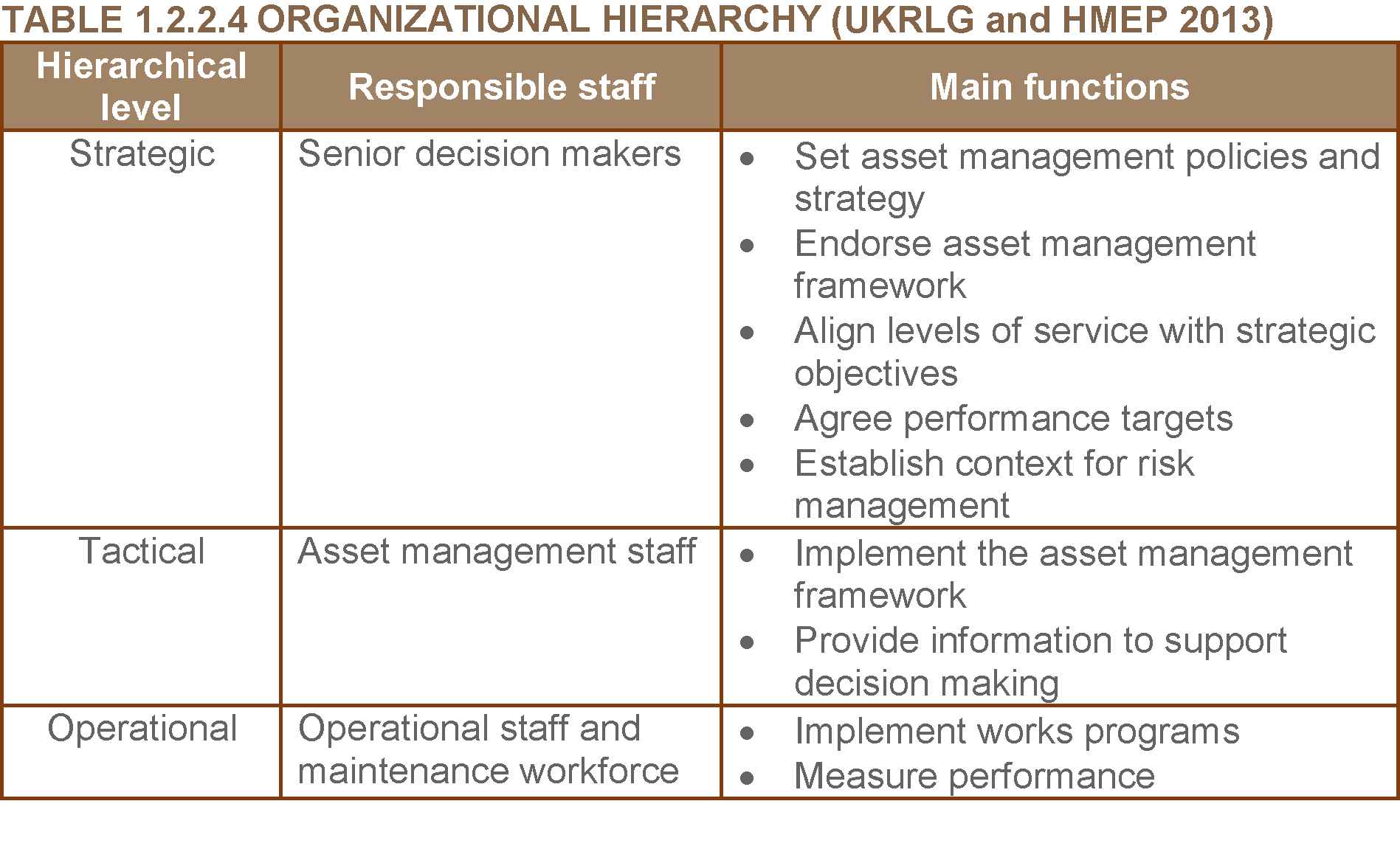

Regardless of the organization type chosen, the roles and relationships driving asset management should clearly establish the strategic, tactical, and operational levels within an organization, as shown in Table 1.2.2.4 (UKRLG and HMEP 2013).

The asset management functions included in Error: Reference source not found are discussed throughout this manual.

Key roles for developing and delivering asset management include the following (UKRLG and HMEP 2013):

The actual positions and relationships among these roles that should be defined within each organization largely depend on the results of the self-assessment exercise.

At the basic maturity level, asset management may rely on just one person or a small group with multi-disciplinary training and experience. As the organization moves to the proficient level, asset management will involve the coordinated effort of various workgroups and multiple individuals.

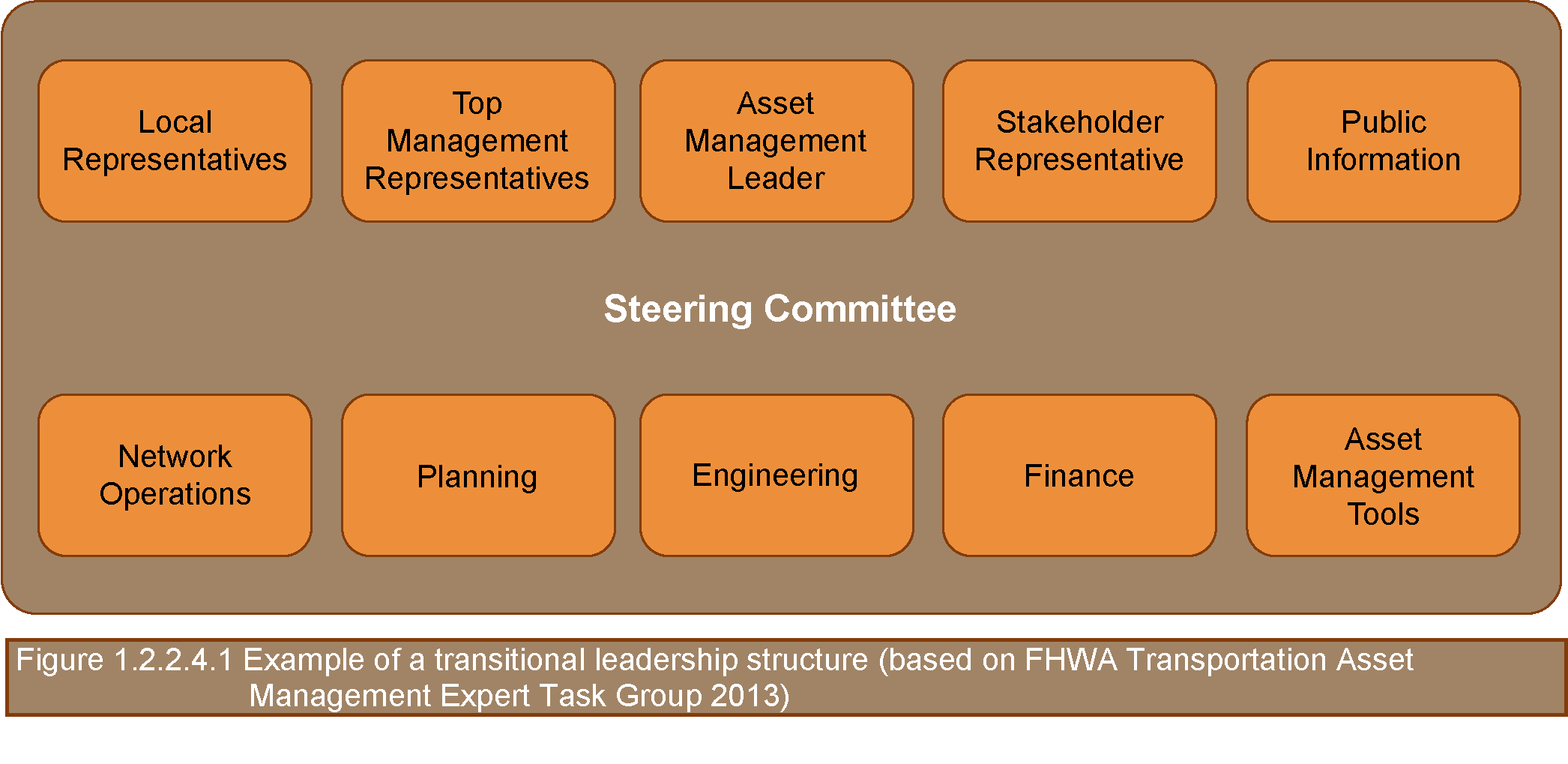

Defining new roles and managing the transition from a small group to a formal, mature asset management team is an important leadership task (FHWA Transportation Asset Management Expert Task Group & AASHTO 2013). It requires a consideration of individual, team, and organizational expectations as well as a vision for how the process will change as the formal asset management team is established and developed. Figure 1.2.2.4.1 shows an example of how a transitional asset management team might be composed.

As with any major project in a road organization, the re-engineering of the corporate structure needs a project manager or project leader, who will be devoting most of his/her time to the project. A feasible candidate to play this role might be the chief executive officer of the organization or a properly empowered senior manager. The most important skill of the project manager would probably be his/her ability to build teams. The attribute list for this person should also include motivation and persistence in overcoming the inevitable barriers that appear whenever an organizational change is attempted. The project manager may come from an engineering, economics, or planning background or, preferably, from a combination of more than one of these disciplines.

A steering committee of senior managers, overseeing the work of the asset management leader, is also essential to ensure that all parts of the asset management process function together as a unit. Sufficient resources are vital to the effective implementation of asset management, including adequate training for agency staff to ensure availability of the necessary skills and understanding to implement asset management successfully.

Clear role descriptions for those carrying out asset management tasks and requirements should then be developed. There is likely to be new competency requirements within the organization and training programs in asset management to support the proposed changes.

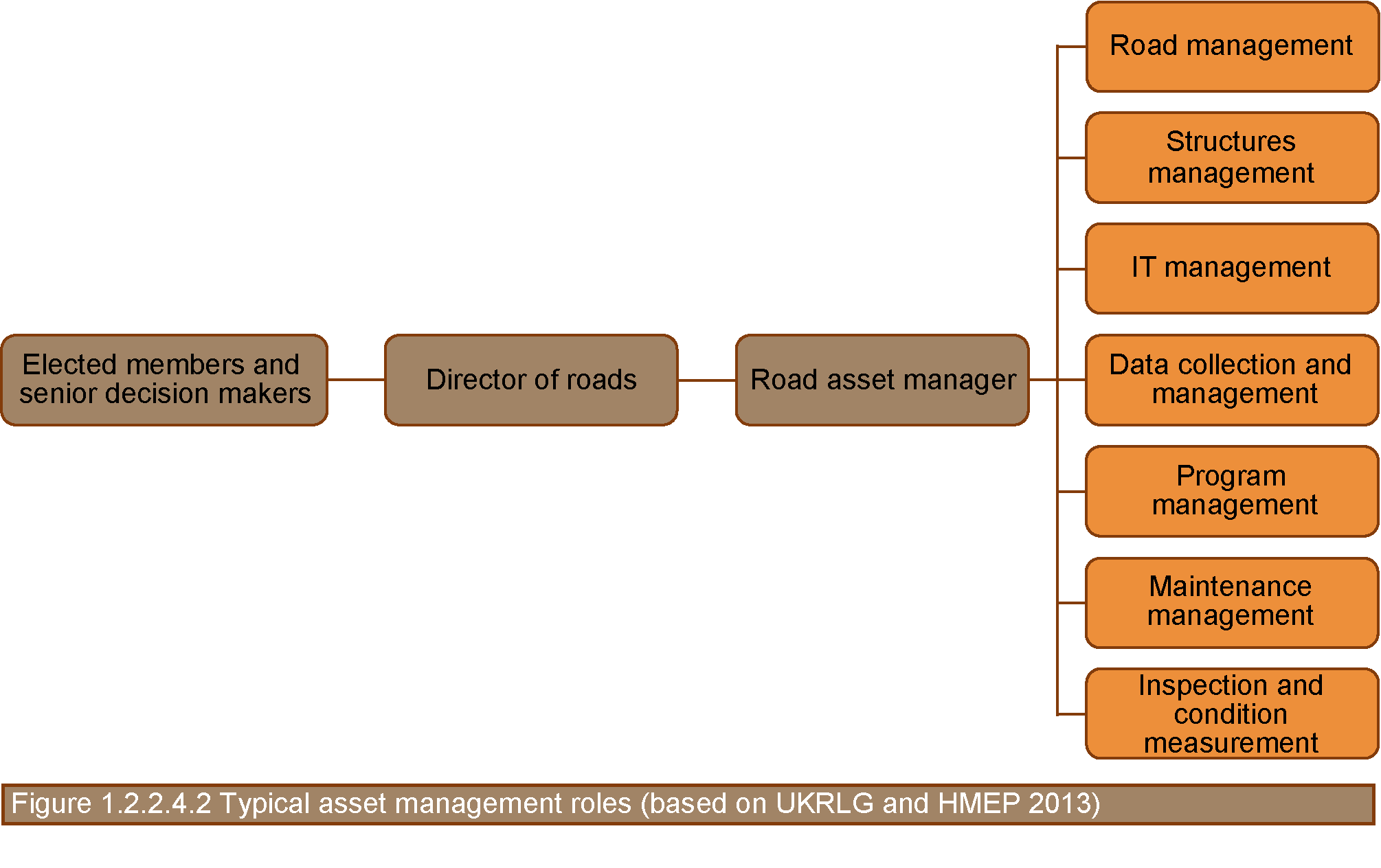

As stated earlier, there is no single way of defining roles for asset management. However, an organizational structure suitable to delivering asset management typically includes the roles depicted in Figure 1.2.2.4.2 (UKRLG and HMEP 2013).

Senior management should identify the competencies necessary to meet the requirements for adopting asset management. Where these competencies are not available in the organization, training of staff may be required. Recruitment, mentoring, or collaboration with other authorities may also be considered (UKRLG and HMEP 2013).

If competencies or resources are not available, external support can be an effective way of addressing gaps, particularly when there is a need to build capability within the organization. It is important that ownership is retained within the agency and that asset management staff have enough knowledge to be smart purchasers.

Competencies may fall under a number of categories, including the following:

There are a number of international training resources for asset management, some of which can be accessed at no cost. These include the following:

Cambridge Systematics, Inc., Applied Research Associates, Inc., Arora and Associates, KLS Engineering, PB Consult, Inc., and Louis Lambert. 2009. NCHRP Report 632: An Asset-Management Framework for the Interstate Highway System. Transportation Research Board of the National Academies. Washington, DC. Last accessed July 24, 2015 at http://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/nchrp/nchrp_rpt_632.pdf.

Cambridge Systematics, Inc., Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Douglas, Inc., Ray Jorgenson Associates, Inc., and Paul D. Thompson. 2002. Transportation Asset Management Guide. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Washingtom, D.C.

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). 2012. Executive Brief: Advancing a Transportation Asset Management Approach. Federal Highway Administration Office of Asset Management. Washington, DC. Last accessed July 29, 2015. http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/asset/pubs/if12034.pdf.

Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) Transportation Asset Management Expert Task Group. 2013. AASHTO Asset Management Guide—A Focus on Implementation. Executive Summary. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Washington, DC. Last accessed July 29, 2015. http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/asset/pubs/hif13047.pdf.

United Kingdom Roads Liaison Group (UKRLG) and Highways Maintenance Efficiency Programme (HMEP). 2013. Highway Infrastructure Asset Management Guidance Document. Department for Transport, London. Last accessed July 24, 2015. www.ukroadsliaisongroup.org/download.cfm/docid/5C49F48E-1CE0-477F-933ACBFA169AF8CB

These practices have been tested in several instances and case studies are being prepared. They will be presented here when available. If you want to share a case study, please contact assetmanagementmanual@piarc.org.